Philip Foner’s May Day: A Short History of the International Workers’ Holiday 1886-1986 was written on the events centennial anniversary. Though there are earlier texts on the history of May Day, Foner’s book seemed like an interesting one to dip into. I don’t cover the entire text, just events leading up to the establishment of May Day. There is much more in the text to cover, and I just skimmed a few parts that caught my attention; these are those notes.

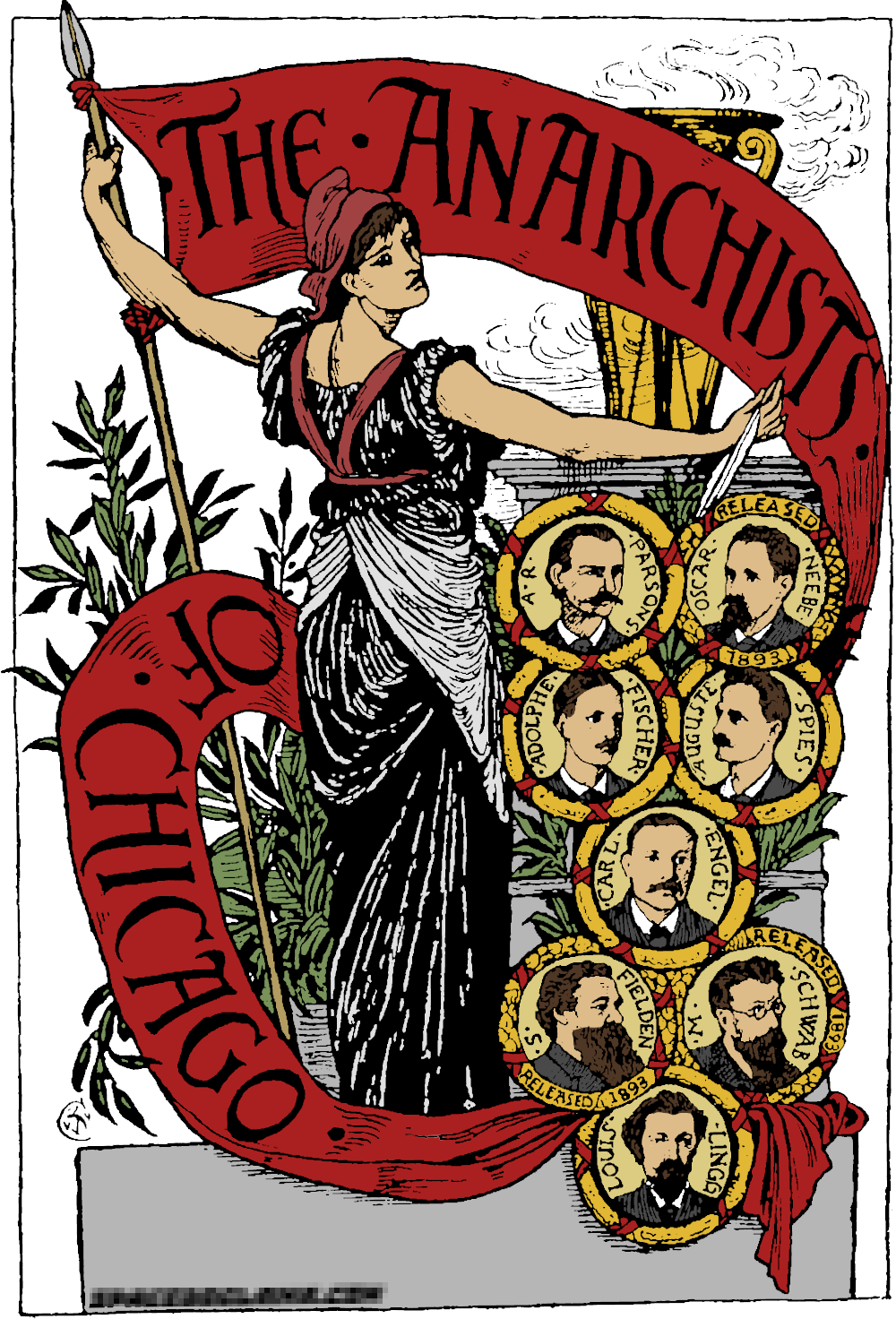

In reviewing the text (Figure 1), I learned that Philip Foner was a noted historian of US labor who wrote more than 100 books. In 1941, he was one of 40 individuals fired from City College of New York for political views following investigations into communist influence in education by the Rapp-Coudert Committee. The committee subponead more than 500 faculty who were interrogated in private hearings, denied legal counsel, the right to cross-examination of other witnesses, or the ability to maintain copies of hearing transcripts. In 1979, the New York State Board of Higher Education formally apologized to Foner and others terminated following the Rapp-Coudert Committee acknowledging that the committee seriously violated academic freedom. Foner’s (1986) book on May Day then was published seven years after this apology. In the 1970’s James Morris documented that Foner’s The Case of Joe Hill plagiarized Morris’s masters thesis. Some have suggested that debates over Foner’s plagiarizing are connected to political disputes. I don’t know any more about that matter.

Foner (1986, 3–4) argues that May Day emerged in the US and began on 1886 as an outgrowth of demands for an 8 hour work day. Before the Civil War [1861-1865], most labor agitation involved calls for a 10 or 9 hour work day (Foner 1986, 9), but there were calls for an 8 hour day from this period as well. To put this into some historical perspective, legal William Wiecek (1998, 46) argues that during the 1860’s and 70’s state Judges, led by Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court Chief Justice Shaw, essentially created torts as a new domain of law to deal with the increased litigation brought on by workplace accidents associated with the industrial revolution. In doing this, doctrines were established that shifted the risks and costs of accidents from employers and producers to labor. This allowed for corporate capital accumulation. “Railroads were the darlings of nineteenth-century judges” Wiecek (1998, 46) argues. Shaw created doctrines that greatly increased the threshold for employee litigation in workplace accident suits. Wiecek (1998, 46) further notes that this shift in liability occurred around the same time that the insurance industry was starting to develop.

In describing the movement for a shorter work day Foner cites several original documents. On of my favorites is from 1827, when Philadelphia carpenters arguing for a reasonable work day wrote:

“that all men have a just right, derived from their Creator to have sufficient time in each day for the cultivation of their mind[s] for self-improvement” (Foner 1986, 8).

To me this assertion feels like a Natural Law argument that references the famous second paragraph of the Declaration of Independence.

Foner writes that by 1863, there were greater steps toward organizing for an 8 hour day. By 1866 there were many 8 hour groups across the US, and in this context Ira Steward emerged as a key figure (Foner 1986, 10). Rather than engage in numerous individual struggles against employers, or even pursue state level fights, Steward pushed for a federal eight hour work day law.

By 1867, several sates passed 8 hour work day laws, but state governments failed to enforce the laws, and the laws themselves were full of loop holes that allowed employers to exempt workers from the laws’ protections. This very much reminds me of Derek Bell’s (2008) arguments regarding the failures of law and courts to deliver meaningful remedies. In 1868 the federal government passed a national 8 hour work day law for federal employees. Those protections did not extend to private sector workers. President Andrew Johnson vetoed the federal worker 8 hour work day act, but it was passed over his veto. Following passage of the law, federal wages were cut. Additionally, the Attorney General ruled that this law did not apply to government contract work. This was disputed, but unanimously upheld by the Supreme Court in 1877 (Foner 1986, 13). During the depression of 1873-1879 employers sought to lengthen the work day.

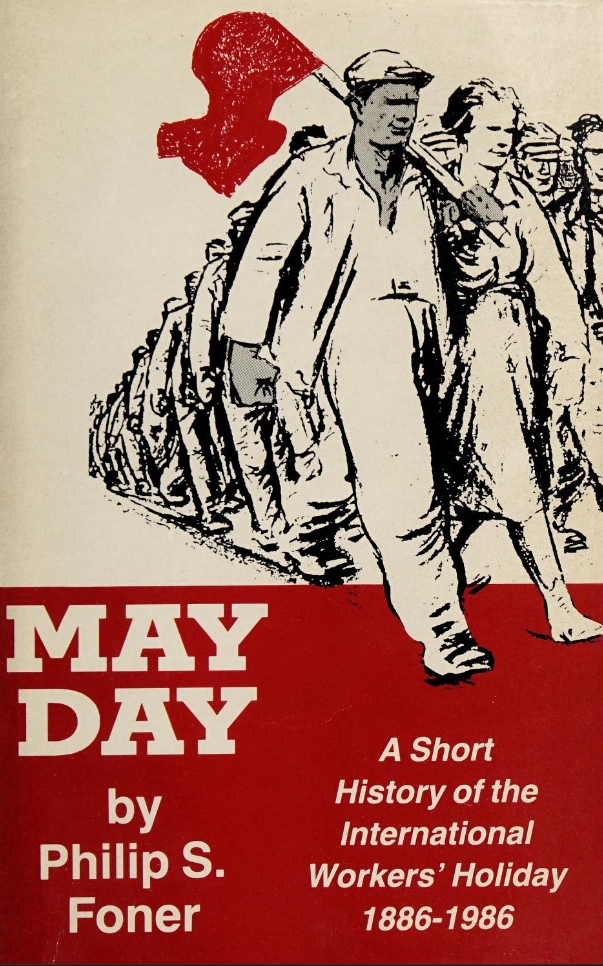

In reading the text, I learned about Johann Most an exiled German Socialist turned anarchist who arrived in the United States in 1882. Most soon became the leader of US labor anarchists and advocated “propaganda by deed” which Foner (Foner 1986, 21) characterized as “individual terror.” A second faction of the anarchist labor movement is known as the “Chicago idea” which combined anarchism with unionism and is viewed as a precursor of anarcho-syndicalism. They concurred that political action was futile and there was value in the use of force. Albert Parsons and August Spies were active figures in the Chicago idea and were later executed in the Haymarket affair.

The effort to establish a reasonable work day continued with opponents of the labor movement expressing concern over communism and sloth. By April of 1886, more than a 250,000 workers were involved in the struggle for an 8 hour work day (Foner 1986, 22). May 1, 1886 was to be a national strike calling for an 8 hour day (Foner 1986, 16). The belief was that waiting for legislation would be in vain, so direct action was needed to press the issue.

On May 1, 1886, large protests were held across the country and followed by extensive strikes. There were two significant police actions: Haymarket Square in Chicago on May 4 and the Milwaukee incident on May 5. In Chicago, a confrontation at the McCormick Harvester plant occurred between the Metal Workers and allied Lumber Shovers on one side and the strikebreakers on the other. Police fired their guns into the crowd killing one immediately and three more workers died later.

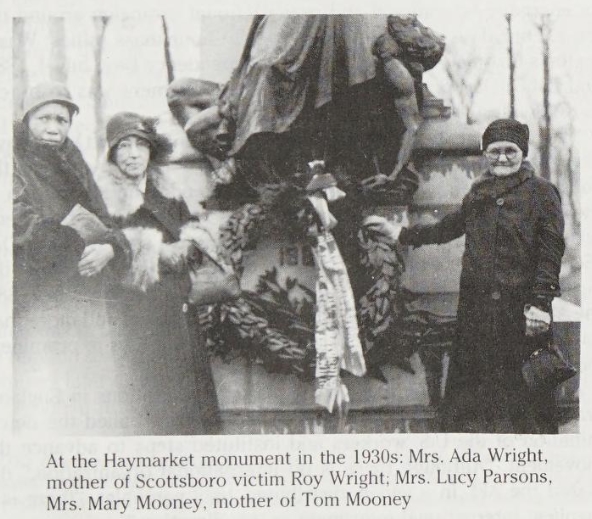

Protests of police brutality against workers were organized for May 4. The protestors were small in number and towards the end of the day police arrived en masse. As the worker’s protest attempted to disperse, a bomb was tossed in front of the police killing one and wounding many more. The police then fired indiscriminately into the crowd killing another and further wounding some already injured police. In a kangaroo court, seven labor leaders were convicted of conspiracy and sentenced to death, an eight was sentenced to life in prison (Figure 2). Engel, Fischer, Parsons, and Spies were hung in 1887. By 1893, Illinois Governor John Peter Altgeld issued a pardon exonerating the convicted and murdered labor leaders as victims of a biased judge and packed jury (Foner 1986, 38–39) (Figure 3).

References

Citation

@online{craig2023,

author = {Craig, Nathan},

title = {Mayday {Post} 2023: {Book} {Review}},

date = {2023-05-01},

url = {https://ncraig.netlify.app/posts/2023-05-01-mayday/index.html},

langid = {en}

}